By Lauren Ohnesorge, Senior Staff Writer for the Triangle Business Journal

Cavernous. That’s how some describe Stage Three at Dark Horse Stages in Wilmington, a purpose-built film production space waiting for a Hollywood director’s “lights, camera, action” call.

Stage Three is a vast space with sweeping concrete floors, black-lined walls and not much else, save a pair of directors chairs with the “Dark Horse” logo. But in a matter of weeks, the space could transform into a western saloon, a quaint village, a graveyard, a space ship soaring across the galaxy — only limited by imagination and a production budget.

“Movie history will be made right here,” says Kirk Englebright, president and CEO of Dark Horse. “You can’t even imagine the movies that will be filmed right where we’re sitting.”

Englebright is an entrepreneur with an if-you-build-it-they-will-come attitude, funneling millions of dollars into a pair of new purpose-built sound stages near Wrightsville Beach. He doesn’t see it as a bet on a company. He sees it as a bet on Wilmington, long known as Hollywood East.

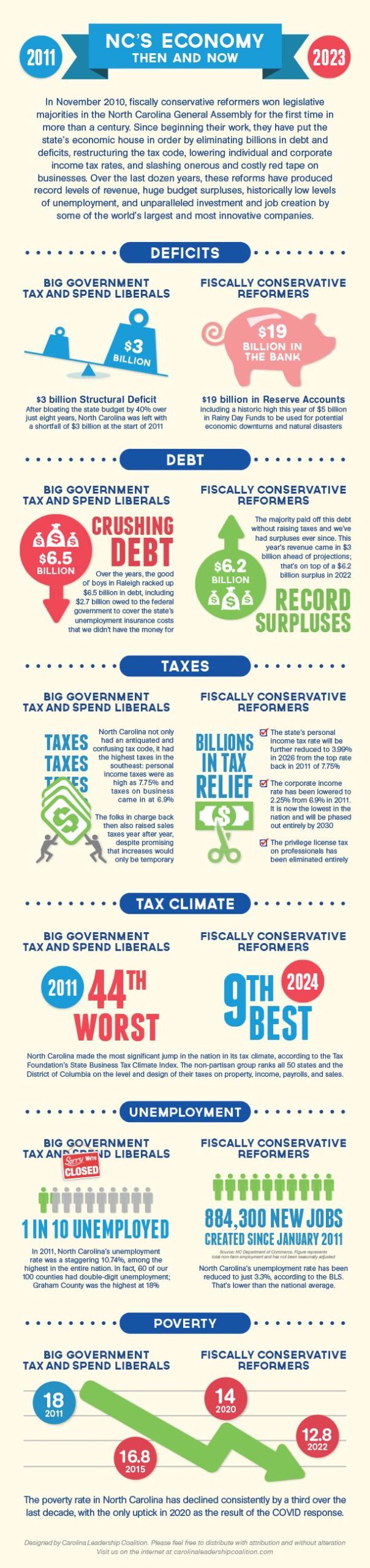

The film and TV industry has a long history in North Carolina, particularly the Wilmington area. According to state data, the film industry has an annual economic impact averaging $179 million and employs around 3,700 people.

As the industry continues to transform with the rise of streaming services, North Carolina is looking to grow those numbers. And with this month’s opening of Stage Three and its mirror, Stage Four, Englebright is about to have his red carpet moment.

The question is: is Hollywood ready to sign on?

Englebright’s Hollywood story starts with Hallmark.

Johnny Griffin, longtime director of the Wilmington Regional Film Commission, remembers when Hallmark called, hungry to shoot in Wilmington. Hallmark needed a place to film, and EUE Screen Gems (acquired in 2023 by Cinespace Studios) was full.

It’s a problem that had happened before in “Wilmywood.” Wilmington had, after all, just one studio complex, its stages once home to productions such as “Dawson’s Creek” and “One Tree Hill.”

Griffin had a proven process in place. He would call Jeremy Phillips, a commercial real estate broker and former director of business development for local economic development organization Wilmington Business Development. Phillips was typically connected and in the know when it came to the warehouse market. He happened to know Englebright had recently purchased a warehouse, the former Coastal Beverage Co. for $4.8 million, and didn’t have a tenant.

“If you have a movie that needs anything, I think it could accommodate them short term,” Griffin remembers him saying.

Englebright, president and CEO of furniture retailer Mattress Capital, knew nothing about the film business. He didn’t have to. The Hallmark deal would be temporary — just some extra cash to tide him over when the pandemic ruined his plan to lease the space to a health care company.

When he heard Hallmark was interested, “All I’m thinking is, you’re going to distribute cards?” But within two weeks of the initial conversation, “They were here in full-blown production,” Englebright said.

Within weeks of the wrap, “I started getting more calls from other productions,” Englebright said.

“They were like, “Hey, we want your space, we want your space,’” he said. “No marketing. … Over the course of the next 36 months, I didn’t have one day of vacancy.”

Big Hollywood projects were filming in his space, hidden on Harley Road just off of the main drag to Wrightsville Beach. They included “George and Tammy,” a 2022 series starring Jessica Chastain, and “Along for the Ride,” a project starring Kate Bosworth. Englebright was hooked. He picked up the phone and cold called Griffin. It was the first time the two men actually spoke.

“He said, I’m going to take this thing off the market and I’m going to turn it into a movie studio,” Griffin said.

Englebright said the business case was obvious.

“We were rocking and rolling and competing at a pretty high level with what we had,” Englebright remembers thinking. “Imagine if we had something worldclass here?”

But building a studio takes work — and money.

Englebright, an Oxford native, came to Wilmington when his company, Mattress Capital, expanded to the coast. He made his fortune selling furniture. His movie knowledge was limited to watching new classics like “Big” with Tom Hanks. Prior to Dark Horse, he collected luxury Italian automobiles — not film memorabilia. The kind of money he’d need to make his vision a reality required a partner.

Englebright estimates $28 million has been sunk into the studio complex, not including office space he has a few miles away.

Englebright teamed up with his longtime friend, business partner and father-in-law, Rodney Long, the CEO and Chairman of Long Beverage to check that box – with the help of Southern Bank.

“[Long] is so pro-business and brings so much knowledge to the table,” he said. “I mean, Rodney has built an absolute empire from the ground up on his own.”

But it also takes demand, something that in an industry like Hollywood is never guaranteed. The rise of streaming services like Netflix has meant an increase in studio builds across the country, meaning competition is increasing. While Wilmington had just Cinespace and its 10 stages, Dark Horse will compete with regions, not just companies. That means competing with Georgia, which boasts 4 million square feet of stage space, primarily in Atlanta. And other regions compete with more than just space — such as aggressive incentive policies.

In North Carolina, grants are limited to $15 million for a television season and $7 million for a feature-length film. In Georgia, there are no limits or caps.

Englebright admits there were a lot of naysayers.

“I’ve already proven them wrong,” he said, pointing to the successful projects Dark Horse has hosted.

But the latest investment, Stage Three and Stage Four, are Englebright’s biggest gambles yet, meaning a whole new set of naysayers.

Prior to breaking ground on the new stages, Dark Horse was profitable. But Englebright said the stages take things to the next level by filling a gap that will get more film investment in North Carolina. Englebright said the elements were all there but one. The region had a worldclass crew base and North Carolina’s film tax rebate to leverage. “But what we were lacking is worldclass, state-of-the-art stages,” he said.

“We said we’d focus on not just building the biggest but the best,” he said. “We took quality over quantity. … And built two that will hold their own with any stage in the world.”

Cinespace’s studio a few miles away was built in the 1980s out of metal. Dark Horse’s new stages are built with 12-inch thick concrete walls with “more steel and rebar than the Statue of Liberty.” They’re lined with thick, garbage-bag looking material, called Insulquilt, to kill noise. The 55-foot high ceilings could support two fully-fueled 737 jets, he said. An exhaust system could clear out smoke from pyrotechnics in seconds. A “silent” noise system allows air conditioning to run soundless in the background of shots. The keyless entry system offers flexibility. A maze of adjacent office space — complete with wardrobe rooms, kitchens, executive suites, warehousing and dailies transmission operations — completes the package.

Is any of it cheap? No. But Englebright is betting filmmakers are willing to pay for the convenience and flexibility.

Griffin said when film companies call his office, they’re not asking about how the studio walls are constructed. But they are asking for purpose-built sound stages, not a warehouse that’s been repurposed. That comes with expectations — that it will have a grid able to hold weight from the ceiling, that it won’t have view-obstructive columns like a typical warehouse.

“They do assume that if it is a purpose-built sound stage then it has normal bells and whistles that come with it,” Griffin said.

Many companies consider their sound studio production stats a proprietary secret, so figuring out what extra bells and whistles to add took research and experimentation. There was no playbook, no instruction manual for just what to build, forcing Englebright to have conversations with anyone who would listen and to make multiple pivots along the way.

Crews have been busy cleaning and painting heavy yellow stripes around the perimeter — an industry requirement. Englebright has had conversations with “all the big names.” He said the studio could be ready to host a production “today.”

Englebright has big expectations.

“This is a massive capital investment,” he said. “It takes time. [Profitability] is not a quick process.”

Englebright said the opportunity for the community is huge. When a film company comes in with a $100 million budget, “they’re leaving with a suitcase. The money has been spent in our economy.”

“The restaurants have served the food, the hotels have put roofs over their heads. … They’re living here, bringing their families with them,” he said.

It’s big business, not just for the skeleton crew he contracts with when a production is in town, but the local crew base dependent on a steady stream of film projects.

Griffin said a new film studio gets attention.

“There’s been one film studio here for over 40 years,” he said. “All of a sudden for another facility to come online, I think it will cause people in the industry to take another look at North Carolina.”

Englebright sees Dark Horse as a company with the potential to transform the region. “We didn’t put up this kind of capital for a hobby,” he said. “This is a major investment.”