There was high drama in Raleigh last week as the Senate failed to override Governor Cooper’s veto of a bill requiring school districts to offer the option of in-person instruction to K-12 students for the remainder of the 2020-2021 school year. The attempt failed by just one vote.

The bipartisan legislation, Senate Bill 37, had passed earlier in the Senate by 31-16 and by 77-42 in the House, both veto-proof margins. The North Carolina Constitution (Article II, Section 22) requires that three-fifths of those legislators present and voting (i.e. a “supermajority”) in both chambers must agree to override a gubernatorial veto. If all 50 Senators are present and voting, 30 are required to reach the three-fifths threshold; if all 120 Representatives are present and voting, 72 are required to reach the three-fifths threshold.

On February 16, three Senators, Ben Clark (District 21), Kirk deViere (District 19), and Paul Lowe (District 32) voted with the entire conservative majority in support of the final version of the bill; a day later, five members of the House minority — Representatives Cecil Brockman (District 60), Charles Graham (District 47), Joe John (District 40), Graig Meyer (District 50), and Shelly Willingham (District 3) — joined all of their colleagues in the conservative majority in support of the final version of the school-opening bill. (The final version of a bill, which resolves differences in earlier versions already passed separately by both chambers, is known as a “Conference Committee Substitute.”)

That same day, the bill was then enrolled. The “enrolled” version is the final version of a bill, which has passed both chambers and is printed in preparation for the actual signatures of the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House. Once this happens, the bill is considered “ratified” and goes on to the Governor for his signature.

Or not. Claiming that it would threaten public health, Governor Cooper vetoed the bill on Friday, February 26.

Follow the Science

But the legislation requires that schools develop three separate situational plans (for minimal social distancing, moderate social distancing, and for remote learning) to address health and safety concerns under guidance from the Governor’s own Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The department itself instructed schools to open for in-person instruction — a directive that was updated just last Thursday, March 4.

And, in a recent report, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) examined eleven school districts in North Carolina with nearly 100,000 students and staff open for nine weeks of (limited) in-person instruction and “found that within-school infections were extremely rare.” Additionally, the study “found no instances of child-to-adult transmission of SARS-CoV-2 were reported within schools.” The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) cited the same findings when it issued its own brief, Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in K-12 Schools: “A study of 11 school districts in North Carolina with in-person learning for at least nine weeks during the fall 2020 semester reported minimal school-related transmission even while community transmission was high.”

Widespread Support

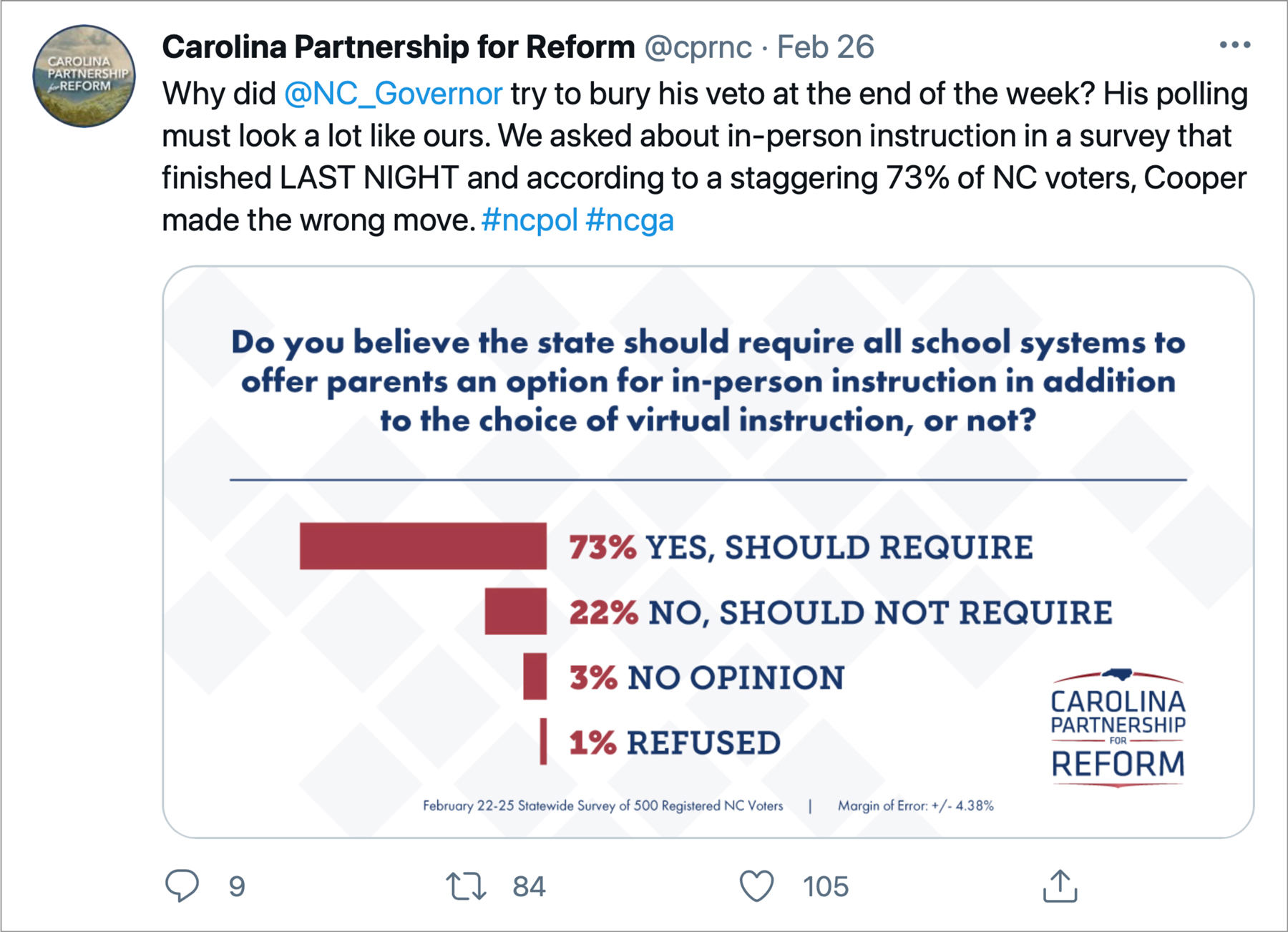

A recent survey by the Carolina Partnership for Reform showed that a whopping 73 percent of its respondents believed that North Carolina should require all school systems to offer parents the option of in-person instruction. These numbers closely align with another recent statewide survey of 500 likely voters commissioned by the John Locke Foundation.

Support for giving parents the option of in-person instruction for their children is in marked contrast to the position taken by the North Carolina Association of Educators (NCAE), North Carolina’s teachers’ union, which enthusiastically supported the governor’s veto.

Follow the Money

Perhaps not coincidentally, the NCAE’s political action committee (NCAEPAC) donated more than the maximum contribution amount allowed by law to Governor Cooper’s re-election campaign last year. This does not include substantial contributions he received last cycle from far-left groups in New York and California, among them George Soros.

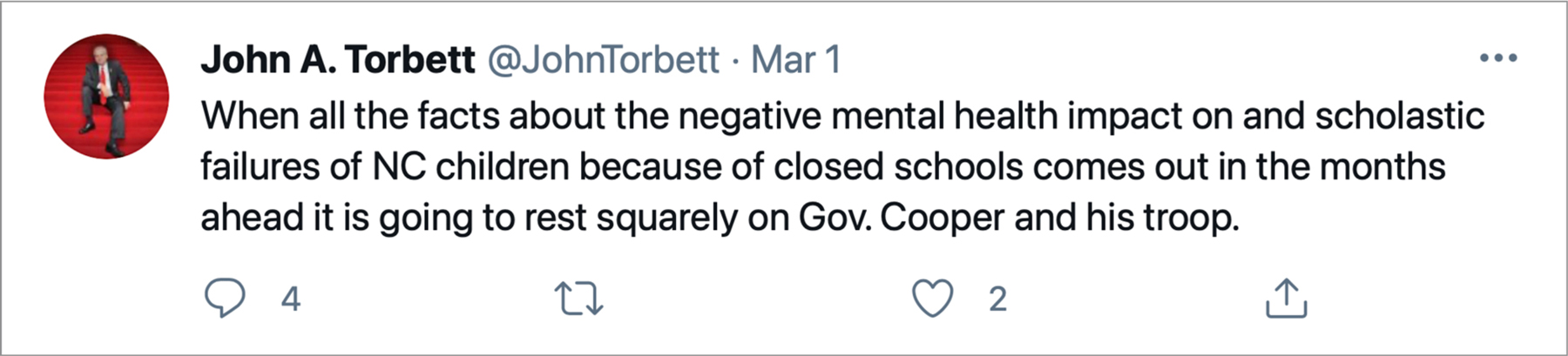

What Happened Next?

The bill returned to the Senate in an attempt to override the Governor’s veto (in such situations, the legislation is returned to the chamber of origin). As the Senate was taking up the override vote, one of the three Senators who had initially supported the legislation (and who happened to be a co-sponsor), Senator Clark, wasn’t on the floor — he had been granted a leave of abscence. And when the vote finally did come, Senator deViere voted to override the veto but Senator Lowe voted to uphold it, despite having voted for the bill earlier. As a result, the override attempt failed by just one vote.

The Big Picture

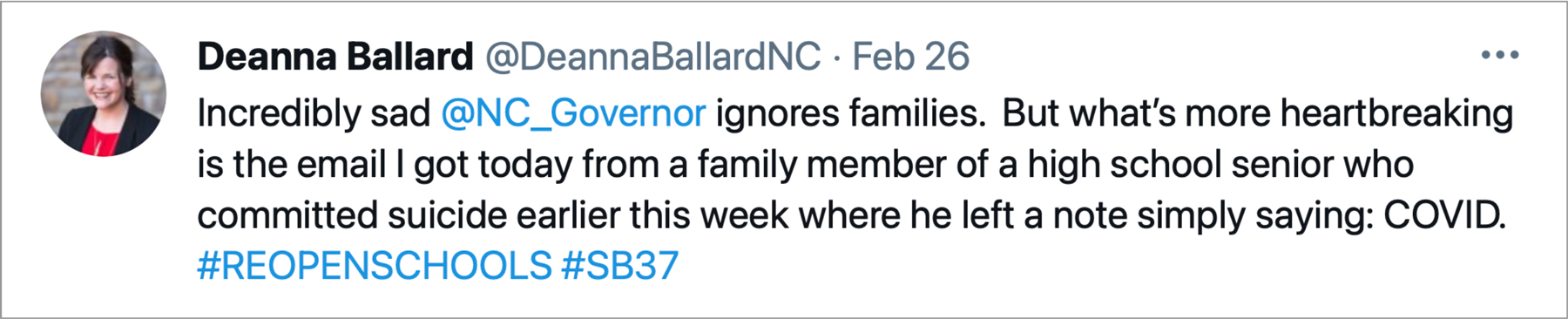

All this political back-and-forth comes as we learn that over half of North Carolina’s high school students failed their end-of-course exams last fall since schools have been closed. Black, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged children have been especially hard hit: for example, in beginning-of-year tests, three quarters of third-grade students aren’t proficient in reading after a year of “virtual learning.”

As if that weren’t enough for concern, there has also been a substantial increase in drug overdoses, self-harm, substance use, anxiety and depression in the last year among children aged 13 to 18, according to a report issued this week by FAIR Health, a non-profit that analyzes insurance claims.

But it’s not over yet. On Wednesday, in a quirk of parliamentary procedure, the Senate voted to reconsider the failed override vote. “Senator Clark will have the opportunity to provide the critical vote necessary to advance his bill over Governor Roy Cooper’s veto,” said Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger.

Stay tuned.