How the Legislature Works

Laws of the state of North Carolina, known as General Statutes, are made by the General Assembly. The General Assembly is a “bicameral” legislature — meaning that it is made up of two bodies: the House of Representatives, which has 120 members, and the Senate, which has 50 members. Each legislator individually represents either a Senatorial District or a House District, and elections are held every two years for each member of the General Assembly. Members come to Raleigh from all kinds of different backgrounds and very diverse professions. The minimum age to be a state Representative is 21, and to be a state Senator, it’s 25. There are no term limits for members of the legislature.

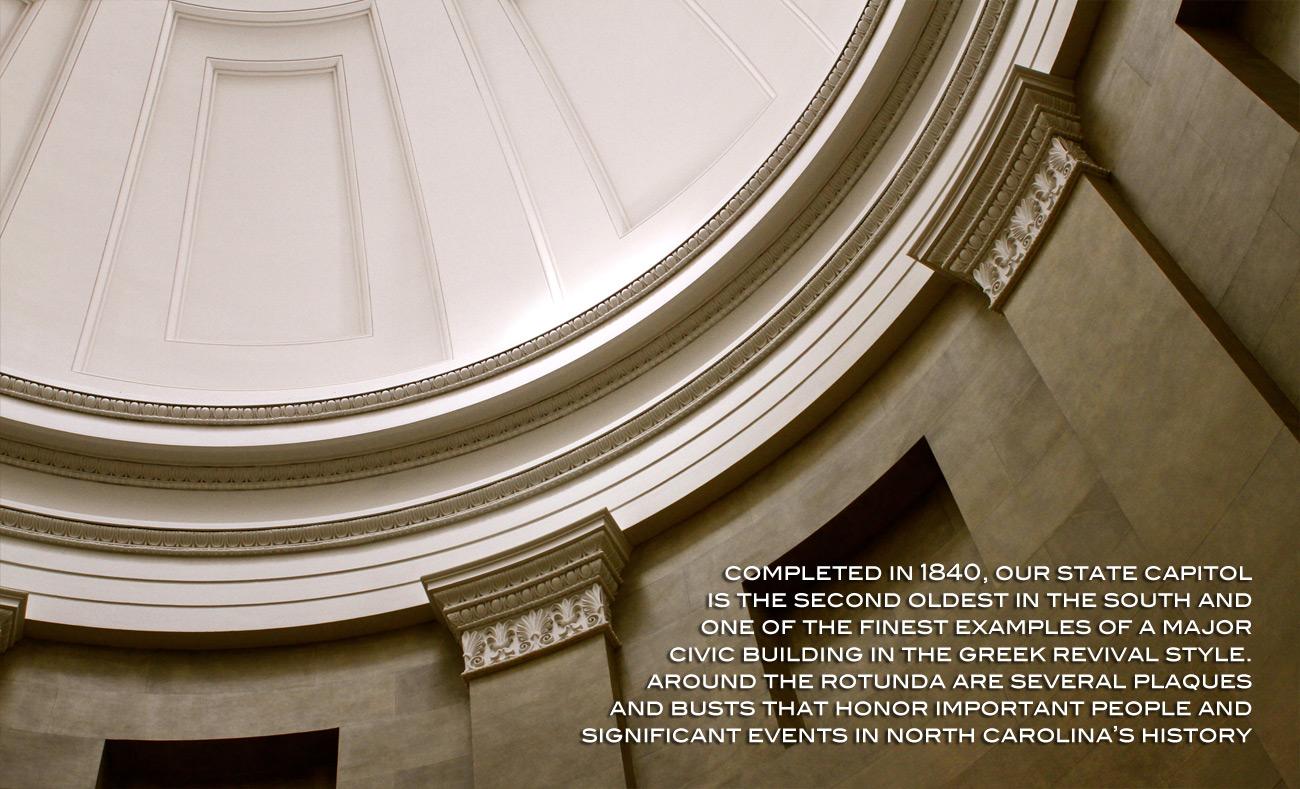

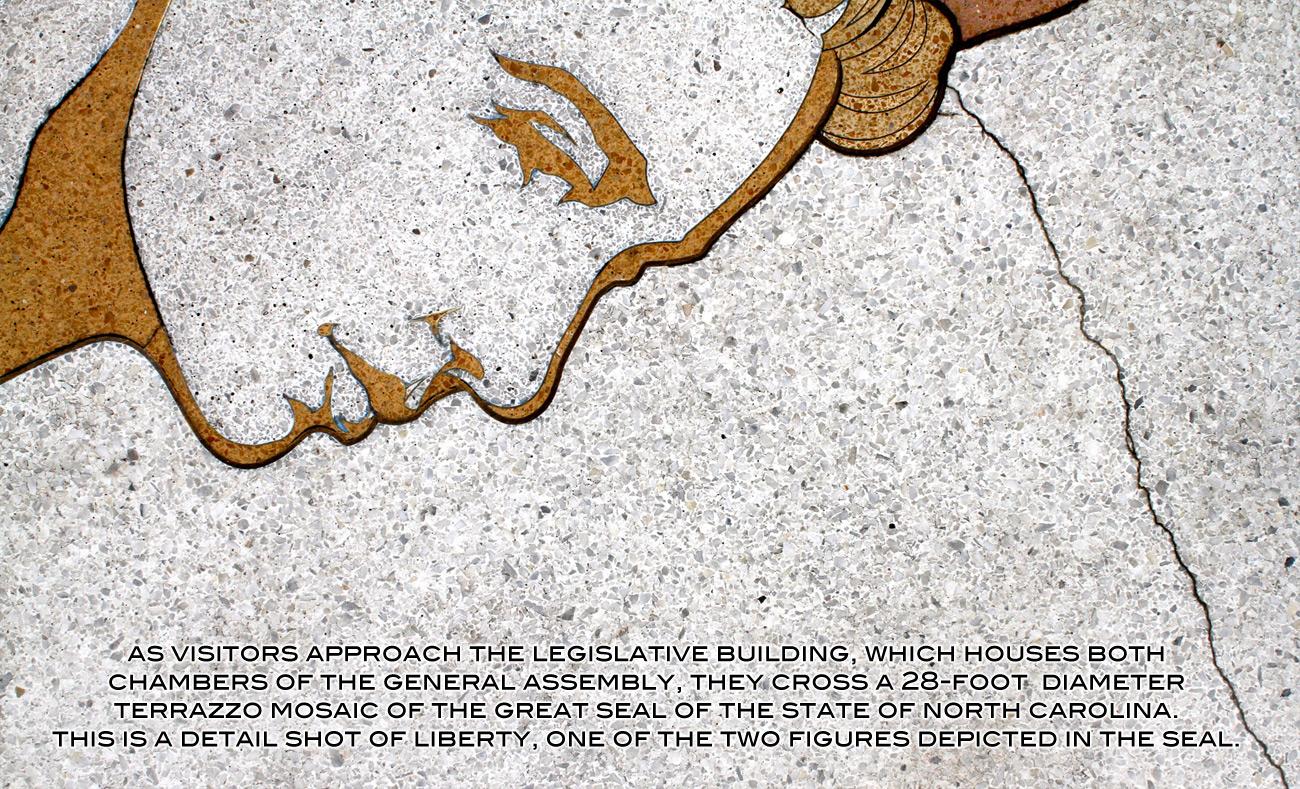

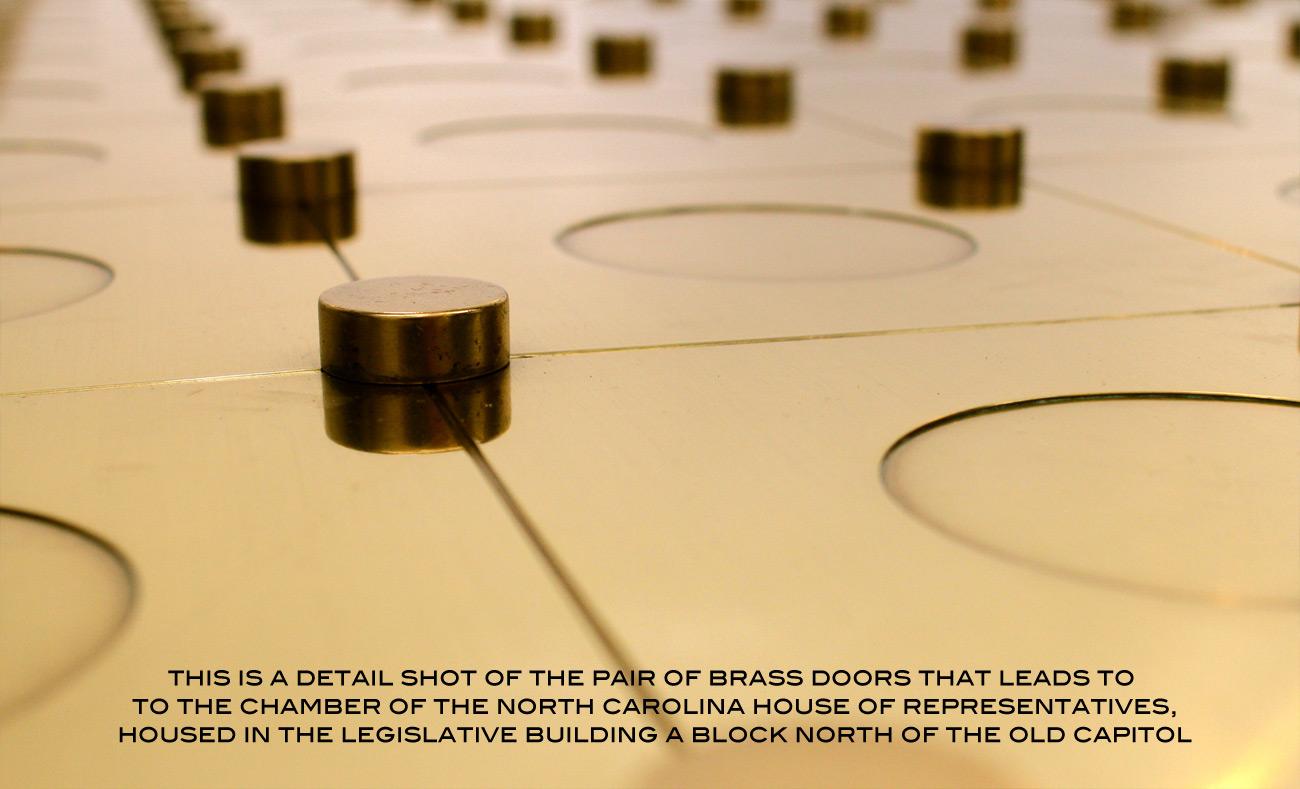

The legislature is housed in the Legislative Building (located at 16 West Jones Street in Raleigh, one block west of the old Capitol Building), which opened on February 6, 1963. Click here for visitor information.

The General Assembly meets over a two year period, called a “biennium.” Its regular session, also called the “long session,” begins in January of each odd-numbered year and lasts roughly six months. After the legislature adjourns for the summer, it reconvenes again the following even-numbered year, usually in the Spring, for what’s called the “short session.” The short session usually only lasts a few months, allowing members to campaign for their reelections.

The North Carolina General Assembly is a part-time legislature, unlike states like California and New York, whose legislatures are in session essentially all year long. Regular members of the General Assembly — as opposed to leadership positions — are each paid just $13,951 per year (click here to view a state-by-state comparison of state legislators’ annual compensation). Each is assigned a legislative assistant (called an “LA” for short) to help them with their work. Audio of the proceedings is broadcast live for both the House and Senate.

The Senate and the House of Representatives meet in their respective chambers on Monday evenings and during the day on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. When the bodies are not deliberating in their respective chambers, committee meetings are held in the morning and late afternoons. Each legislator is assigned to one or more committees, depending on their interests, background, and areas of expertise. The lion’s share of the legislature’s work is done in committee meetings, and many committees continue their work throughout the year, even when the General Assembly is not in session. Audio and video for most House committee meanings is live-streamed; one can find links to these broadcasts on the most current Legislative Calendar. One may also sign up to receive email alerts and email notices on each committee’s web page.

Members typically return to their homes on Thursday afternoons — after the week’s session has ended — to take care of their personal affairs and to make themselves available to their constituents.

Types of Statutes

By following proper procedures and observing Constitutional limitations, the General Assembly can make new laws and can repeal old ones. The kinds of laws which are enacted can be classified under five general categories:

- Laws regulating individual conduct. These laws prohibit certain acts or require certain acts by an individual in order to promote the interests of society. These laws frequently impose a penalty for violations: a fine, imprisonment, or both. These are also known as criminal laws.

- Laws providing for State services. These laws include provisions for schools, hospitals and health services, agricultural and industrial research, public recreation facilities, and many other types of services which the State may provide for its people.

- Laws empowering or directing local governments to act. Cities, counties, and many other types of local governmental units are creatures of (created by) the General Assembly and are ultimately subject to state control. This control is generally exercised through the General Assembly by enabling or directing the cities and counties to act in the manner desired by the State.

- Laws determining how much money will be raised by the State and for what purposes it shall be spent. When the General Assembly enacts the various tax (revenue) and appropriations (spending) bills, it makes two determinations: 1) How much of the resources of the people of the State will be taken for purposes of government, and b) which state governmental services will get priority for available funds.

- Amending the State Constitution. In addition to these four types of statutes, the General Assembly may propose amendments to the State Constitution. If an act to amend the Constitution is approved by at least three-fifths (72 members of the House and 30 Senators) of the total membership of each body, the proposal is then voted on by the citizens of the entire State in a referendum on election day. If a majority of the voters approve it, the proposed amendment then becomes part of the Constitution. Read a history of North Carolina’s Constitution here.

Introduction of Bills

A bill is a proposed law. Anyone can propose an idea for a bill to a legislator: a private citizen, a corporation, a professional association, a special-interest advocacy group, a state agency or even a city or county. But all bills must be sponsored by one or more legislators to be considered by the General Assembly. A bill may be drafted by any competent person, although the Legislative Services Commission’s Bill Drafting Division drafts bills at the request of the members of the General Assembly. The Office of the Attorney General has the statutory duty to draft bills at the request of the state’s many departments and agencies (called “agency bills”), and for the General Assembly in general. This means that legislators have two separate offices to which they may turn for drafts of bills. However, most every bill filed is drafted or re-drafted by the Legislative Services Commission before being introduced.

Only a member of the General Assembly may introduce a bill – that is, present it to the General Assembly for its consideration. That legislator is called the bill’s Primary Sponsor. Up to three other legislators may join the first-position Primary Sponsor as Sponsors of the bill, but an unlimited number of members can join the Sponsors as “co-sponsors” of the bill.

A member wishing to introduce a bill must have first filed it with the Principal Clerk’s office on the previous legislative day. There, it is stamped with an official number and logged-in electronically for tracking purposes so that legislators and the public can more easily follow its progress. When the body goes into session, the presiding officer (the Speaker of the House or President of the Senate or their designees) announces the time for the “Introduction of Bills and Resolutions.” The Reading Clerk then reads aloud the name of the bill’s sponsors, the bill’s number, and the bill’s title — at this point the bill has passed its First Reading. Typically, just the title is read aloud (as opposed to the entire bill) for the sake of brevity — as legislation often runs to many thousands of words and hundreds of pages. Before technological advances like photocopiers and the Internet, bills were read in their entirety. All members receive full electronic copies of the bill.

The Path to Becoming Law

After the bill passes its First Reading, it is immediately assigned to a committee (or committees) for consideration. Committees are where the real legislative work in Raleigh occurs, as policymakers consider the merits of a bill. This is also the stage where experts, advocacy groups, and the general public can offer input.

As the committees undertake their work, they often make significant changes to the bill; these changes ultimately end up in what’s called a “proposed committee substitute” (PCS) of the original bill. Committees are also where the real power in the legislature is exercised. If a committee decides to kill a bill, the bill “dies in committee.” The bill “passes committee” if the committee votes to give the legislation a “favorable report.”

After a bill passes a committee favorably, it often will be considered by further committees, where it may be altered yet again before its next, or Second Reading. This committee process can be lengthy, sometimes taking weeks or months. The Speaker of the House and the Chairman of the Rules Committee in the Senate have enormous discretion over what committees a bill is assigned to on its path to becoming law, but bills are usually assigned to committees based on the nature of what the bill is written to do. For instance, all bills seeking to raise a tax or a fee must pass through the Finance Committee, and all bills that spend taxpayer money must go to the Appropriations Committee. The most powerful committee in terms of the legislative process is the Rules Committee: this committee can choose to intervene at any time. There’s an old expression that it’s the Rules Committee where bills go to die (or, as it happens, be reborn).

If the committee approves the bill, it reports this fact to the presiding officer, who may (or may not) place it on the Calendar (the daily schedule of business) for consideration by the full membership of the body. Additional changes to the bill (called amendments) may be recommended by the committee or may be proposed by any member from the floor.

Second Reading occurs after the bill has successfully passed through this sometimes complicated maze of committees. The bill is “read for a Second Time” and is then fully debated by legislators on the floor. When the time comes for a consideration of the bill by the full membership of the body, the presiding officer will recognize the sponsor of the bill or the chair of the committee which recommended the bill for passage. That person explains the bill, and then any member who wishes to speak for or against the bill will be heard.

The presiding officer manages the floor debate according to well-established customs and procedures (although sometimes the Speaker of the House or the President of the Senate will designate another legislator to perform this task), recognizing in turn members who wish to speak on the matter in question (by asking “For what purpose does the gentleman (or gentlelady) rise?”). The length and liveliness of debate usually depends on how contentious the bill is, but in reality, the vast majority of bills are not very controversial and there is virtually no debate at all, because many members have become familiar with the provisions of the bill from their committee work. During this process, legislators may offer amendments to the bill (which are voted on by the body separately). An “engrossed” bill contains all the adopted amendments and other changes that were incorporated into the bill as it makes its way through the Senate or House of Representatives.

When the floor debate ends, the presiding officer calls for a vote by commanding that “All in favor, will vote (or say) aye, all opposed, no.” Depending on the type of vote, members will then either vote verbally (called “Viva voce,” from the Latin meaning “with living voice”) or by using one of two small electric switches at their desks which are located on the floor of the chamber. Members must be physically present and at their desks to vote. Members press a green button for an “Aye” vote and a red button for a “No” vote. Members typically have only five seconds to cast their vote; if a bill passes its Second Reading, it receives preliminary approval…but is still not yet law.

Third Reading is the point at which a bill is read with all its amendments, providing further time (if necessary) for additional deliberation by the body before a final vote is taken. In some cases, a bill must wait until the next legislative day to be read a Third Time. Any bill which seeks to raise a tax or a fee must get its Third Reading on a separate day. Under normal circumstances — and if there is no objection by a member of the body — a bill is typically read for a Third Time immediately after it passes its Second Reading vote. Sometimes a member may object to the same-day Third Reading as a delay tactic, in which case Third Reading occurs the next legislative day. (A “legislative day” is when the body is in session. Typically, legislative days do not include Fridays, Saturdays, or Sundays.)

Crossover

“Crossover” refers to an important date that followers of legislative action should be aware of.

This year, the crossover deadline in the North Carolina House of Representatives is Thursday, May 13th. This is the date by which a bill must pass either the House or the Senate in order to remain eligible for consideration in the remainder of the session. The bills that do not pass one chamber or the other by this date are effectively dead for the session.

However, if a bill fails to make the deadline, the idea contained in the bill is not necessarily dead. The deadline impacts the specific bill number associated with the idea. The idea itself could possibly be included in another bill that has already passed one chamber, or it could be added to a different but related bill later in the session.

Once crossover occurs, the North Carolina General Assembly’s non-partisan central staff publishes a list of bills that remain eligible in the session. That list will be available on the legislative website at www.ncleg.net after the deadline passes.

The historical purpose behind the crossover date seems to be in limiting the overall length of the session. In North Carolina, a specific date for session adjournment is not set by the body. However, service in the legislature is meant to be a part-time position for the elected members and establishing a crossover deadline can be viewed as helpful in reducing the overall length of the session — and allows members to return to their full time professions and family responsibilities in a reasonable amount of time.

Consideration of the Bill by the Other Body

After a bill has successfully passed its Third Reading in the body in which it was first introduced, it is then officially sent to the other body (e.g. a bill originating in the House then goes to the Senate). There, it goes through exactly the same process all over again – that is, it is “read in” for the First Time, referred to a committee or committees, and if the reports are favorable along the way, it’s debated and voted on again by the other body during its Second and Third Readings on the floor. The bill must successfully make it through this entire complicated process in both chambers before becoming law.

Bills which passed one chamber might not even be taken up by the other body, consigned to languish in some committee never to be heard from again. An idea from one bill can be folded into another, unrelated bill; in the waning days of a legislative session, this maneuvering can get complex as language jumps from one bill to another on its final journey to becoming law. A bill that was originally drafted for one purpose in the House might end up taking on additional provisions dealing with seemingly unrelated matters from the Senate, and so on. But this is the nature of lawmaking — and everything happens according to (or because of) very specific House and Senate rules.

Concurrence

If the second body makes changes to a bill that was passed by the body in which the bill first originated, it must be returned to the body of origin, with a formal request that the originating body “concur” (agree) with the changes made by the second body. Even at this stage, those changes can be either technical or substantive. Sometimes the second body adds entirely new provisions to the bill or guts the bill entirely.

If the original body objects to the changes made in the other body, the two presiding officers may appoint members to a “conference committee” which seeks to reconcile the differences between the two bodies. If the committee can agree upon the disputed subject, the conference committee reports back to each body, and the two houses vote on the recommended text. If either body rejects the conference committee’s recommendations, new members may then be appointed to the conference committee to try again. Otherwise, after all that time and work, the bill is defeated.

If the original body concurs with the changes, the bill is ready to be “enrolled” and signed into law.

Enrollment, Ratification, and Publication

After a bill passes both chambers, it is enrolled (enrolling is the process of changing a bill which has passed both chambers into its final format). A clean copy (including all amendments) is prepared, with space for the signatures of the two presiding officers, and the Governor, if necessary.

The enrolled copy is taken to the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate during the next daily session. Each presiding officer signs the enrolled copy. When the second signature is affixed, the bill is said to have been “ratified.” If the bill is Local Bill (affecting 15 counties or fewer), it immediately becomes law.

In 1996, the citizens of North Carolina voted to amend the state Constitution, giving the Governor limited veto power (see Article II, Section 22 of the North Carolina Constitution). Prior to that time, the Governor could not veto anything passed by the General Assembly, and North Carolina was the last state in the union to grant its governor veto power. The Governor’s veto power is limited in that only certain bills are subject to it, including Public Bills (affecting 15 counties or more), but not including any bills which make appointments (to official state boards or commissions, for example), propose state or federal constitutional amendments, or redraw state or federal electoral districts. In North Carolina, the Governor lacks the power to veto a Local Bill.

The day after a bill is ratified, it is presented for the Governor’s approval or veto. If the Governor signs the bill or takes no action on the bill within ten calendar days, the bill then automatically becomes law. After the General Assembly adjourns for the summer, the Governor has just thirty calendar days to act on a bill. The Governor is required to reconvene the General Assembly if a bill is vetoed after adjournment, unless a written request is received and signed by a majority of the Members of both bodies that says it is not necessary to reconvene. In North Carolina, the Governor lacks the power to veto just a part of the bill (called a “line-item veto.”)

If the Governor vetoes a bill, the bill is returned to the original body, where three-fifths of the members present and voting(as opposed to the entire total membership of the body) can vote to override the veto. If the original body votes to override the veto, the bill is then sent to the second body, where three-fifths of those members present and voting must also vote to override the veto before the bill can become law. A member of the body may be present, but for whatever reason choose not to cast a vote one way or the other. As a result, his or her presence is not counted against the three-fifths required to override the veto. Technically speaking, it’s possible for a single member in each body to affect a veto override — that is if no other member of each body chooses to cast a vote.

After the bill becomes a law, the term “bill” is no longer used (although the bill number can still be used to retrieve the text of the new law on the General Assembly’s website). The enrolled law is given a chapter number and is then published under that number in a volume called “Session Laws of North Carolina.”