By CLC staff

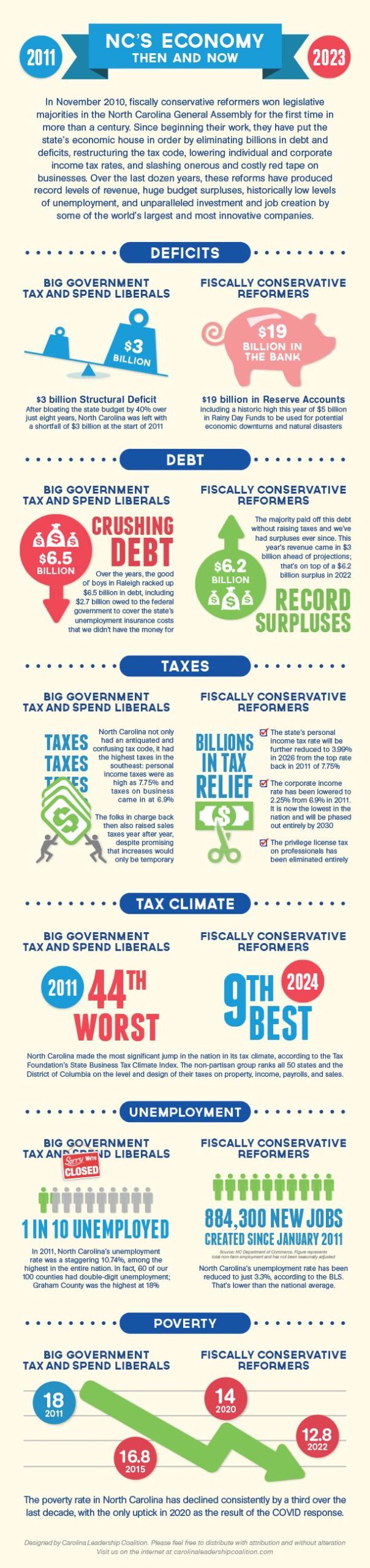

Yesterday’s editorial in the Wall Street Journal sings the praises of North Carolina’s ongoing tax reform efforts, something we do regularly on these pages. The conservative majority has delivered incremental reductions to the individual income tax rate over the last decade, which are now the lowest individual income tax rates in the South Atlantic Region. The Journal’s Editorial Board puts it thus:

“North Carolina has cut its income tax in several rounds in the past decade — from 7.75% in 2013 to 4.5% today and 3.99% starting in 2026. That’s transformed the state from a high-tax outlier to the belle of the ball among regional contenders like South Carolina (6.5%) and Virginia (5.75%). It also reduced its corporate tax rate to 2.5% from 6.9%, and it will drop to 1% by 2028.”

But there’s a more troubling aspect to the piece. The editorial warns of an effort by a certain candidate running for governor to revive North Carolina’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The state EITC was ended on January 1, 2014 by the conservative majority as part of its historic Tax Reform package enacted in 2013. [Editor’s note: people are still eligible to receive payments under the federal EITC program.]

Several bills have also been introduced this session in the General Assembly that would not only reinstate but expand North Carolina’s EITC: House Bills 479 and 541 and Senate Bills 497 and 461.

Thankfully, like the dozens of other pieces of legislation over the last ten years attempting to reinstate North Carolina’s EITC, it doesn’t look like this batch is going anywhere soon as they are all currently gathering dust in the Rules Committee basement. The Journal’s editorial quotes House Speaker Tim Moore as saying, “We’re not going to bring that back.”

Background to the Wall Street Journal Editorial

North Carolina’s version of the EITC was first enacted in July 2007 by the General Assembly a year before the Great Recession hit. Fiscal conservatives opposed the extension of North Carolina’s EITC’s program as being reckless and unsustainable: between 23 and 28 percent of all state EITC claims were paid in error.

According to one estimate, because of errors and fraud, state EITC programs cost taxpayers more than $1.3 billion. A report by the United States Treasury Department’s Inspector General at the time showed that 25% of EITC payments were made in error, amounting to more than $13 billion in wasted taxpayer dollars (by way of comparison, the food stamps program has an error rate of below five percent over the same period).

And from a 2015 Cato Institute report:

“The EITC has a high error and fraud rate, and for most recipients it creates a disincentive to increase earnings. Also, the refundable part of the EITC imposes a $60 billion cost on other taxpayers, reducing their incentives to work, invest, and pursue other productive activities. We conclude that the costs of the EITC are likely higher than the benefits. As such, the program should be cut, not expanded. Policymakers could better aid low-income workers by removing government barriers to investment, job creation, and entrepreneurship.”

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a public assistance program for lower-income folks who are employed. There are many other types of government assistance programs for lower-income people who do not or cannot work (in Fiscal Year 2022, the federal government spent more than $1 trillion a year on more than 80 welfare programs, not including Social Security and Medicare); but to qualify for the EITC, you must have a job — hence the term “earned income.” The EITC is calculated as a percentage of that earned income.

The EITC comes in two forms: the federal EITC and, in some cases, a state EITC. 32 states and the District of Columbia currently offer their own EITC payments on top of payouts from the federal EITC program.

The federal EITC program was first established in 1975 during the Ford administration as an attempt to reduce poverty in a time of rising food and energy prices. It has been expanded greatly by every congress since: in fiscal year 1976, its total value was $1.1 billion; as of December 2022, its value was more than $57 billion.

Although the EITC was intended as a temporary program, in the 1990s, it became a major component of federal efforts to reduce poverty. It is now the country’s largest anti-poverty cash entitlement program: nationwide, as of December 2022, approximately 22.6 million taxpayers received about $57 billion in federal EITC dollars.

Both the federal EITC and the various state EITCs come in the form of what’s called a “refundable tax credit.”

A tax credit is an amount that’s deducted from the amount of taxes you owe. For example, if you owe $100 in taxes but you qualify for a tax credit of $25, you would only owe $75.

Despite its name, a tax deduction isn’t actually deducted from the amount of taxes you owe. A tax deduction is an amount that reduces the taxable income on which your taxes are based. For example, if your annual income was $50,000 and you claim a deduction of $5,700, then your taxable income would be $44,300 ($50,000 minus $5,700 = $44,300). Put another way, a deduction is an amount of your income that cannot be taxed.

Depending on what tax credits and deductions are claimed, the amount of tax a person owes (called the “tax liability”) can even get down to zero.

Refundable tax credits like the EITC are contrasted with nonrefundable tax credits. The vast majority of government tax credits are nonrefundable — meaning that although they reduce a person’s tax liability, the amount isn’t refunded to the taxpayer. With a refundable tax credit like the EITC, it is.

A “refundable tax credit” is not just an amount that is deducted from the amount of taxes you owe, it is directly paid back to an individual — hence the term “refundable.” Basically, rather than withholding the tax, the money is available with your paycheck. (Not to confuse the matter even more, but strictly speaking, the amount that is paid back through a refundable tax credit isn’t really refunded — it is paid beforehand. A refund suggests paying something in to get something back. But unlike a “tax refund” — the total amount you overpaid in taxes with every paycheck throughout the year and which the government owes you back — recipients of refundable tax credits like the EITC can get their check before paying anything in — if they pay anything in at all.)

For the current (2023) tax year, the federal EITC payment to a both a single person and married persons filing jointly without qualifying children is $632. The federal EITC payment goes up to $4,213 with one child; $6,960 with two children; and $7,830 with three or more children. In North Carolina, 786,000 North Carolinians claimed the federal Earned Income Tax Credit last year with an average amount of $2,585.

To qualify for the federal EITC program for the current tax year, a person must be working and their earned income and adjusted gross income must each be less than:

- $56,838 ($63,398 married filing jointly) with three or more qualifying children

- $52,918 ($59,478 married filing jointly) with two qualifying children

- $46,560 ($53,120 married filing jointly) with one qualifying child

- $17,640 ($24,210 married filing jointly) with no qualifying children

Eligibility requirements for state EITC programs generally mirror that of the federal program. In other words, if you are eligible to receive federal EITC payments, you are also eligible to receive additional money under a state’s EITC program (if one is offered). If the federal government expands its EITC eligibility to include more people (which it has many times), the state’s EITC programs are forced to necessarily grow at the same time.

The states which offer their own EITC payments (on top of the federal EITC payment) calculate their amounts based on a percentage of the federal EITC. It varies greatly by state: on the high end of the scale, California’s EITC pays an additional 45% of the federal EITC, the District of Columbia’s pays an additional 40% of the federal EITC, Minnesota pays an additional 25% to 45% of the federal EITC, and New Jersey pays an additional 40%. On the lower end of the scale, Montana pays an additional 3%, Louisiana and Oklahoma pay an additional 5%, and Michigan pays an additional 6%

When the EITC was first instituted here in 2007, North Carolina paid out an additional 3.5% of the federal EITC; the amount was then increased in the 2008 short session to pay out 5% of the federal EITC. In 2012, the Obama administration expanded eligibility for the federal EITC program; in response, in 2013, the General Assembly trimmed back the rate at which the state paid out its EITC benefits from 5% to 4.5%.

According to the Wall Street Journal’s editorial, the total cost of the program — if it’s reinstated — could cost the state more than $465 million a year.